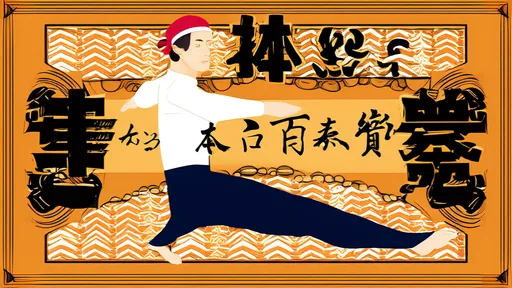

The ancient practice of Zhan Zhuang, or "standing like a tree," has been a cornerstone of traditional Chinese martial arts for centuries. While its roots lie in combat training and energy cultivation, modern sports science is beginning to uncover the profound biomechanical and neuromuscular benefits hidden within these seemingly static postures. What appears as simple standing to the untrained eye reveals itself as a sophisticated system of whole-body integration when examined through the lens of contemporary kinesiology.

At its core, Zhan Zhuang challenges conventional Western exercise paradigms by emphasizing stillness over movement, internal awareness over external performance. The various standing postures - from the basic Wuji stance to more advanced positions like Hugging the Tree - create specific alignment patterns that stimulate the body's myofascial networks in unique ways. Sports scientists now recognize these postures as active isometric contractions that engage multiple muscle chains simultaneously, promoting what modern trainers call "structural integrity."

The postural alignment in Zhan Zhuang creates a continuous tension-compression dialogue throughout the body's kinetic chain. When practitioners maintain the characteristic slight knee bend and pelvic tilt, they activate the deep stabilizer muscles in a manner remarkably similar to modern core stabilization exercises. However, unlike isolated core work, the standing practice integrates this activation with proper diaphragmatic breathing and ground force connection - elements that sports medicine now considers vital for functional movement.

Traditional masters spoke of "song" (relaxation within structure) as the essential quality to cultivate during standing practice. Modern electromyography studies reveal this corresponds to the balanced co-activation of agonist and antagonist muscle groups. The subtle adjustments practitioners make to find this equilibrium mirror the proprioceptive training used in elite sports rehabilitation. This may explain why many martial artists who practice Zhan Zhuang demonstrate exceptional body awareness and injury resilience.

Ground reaction forces play a crucial role in Zhan Zhuang's effectiveness, though this aspect was never articulated in classical texts. The slight forward lean and weight distribution prescribed in various stances create optimal loading conditions for fascial rebound. Sports scientists note similarities between these principles and those employed in plyometric training, albeit at much lower intensities. The standing practice appears to condition the body's elastic tissues through sustained, low-level tension rather than explosive movements.

The rotational components hidden within seemingly static postures particularly fascinate modern researchers. When practitioners focus on the traditional concept of "six-directional force," they unconsciously engage in what kinesiologists call "rotational stability drills." The subtle spiraling tensions maintained throughout the body during standing practice develop the same kind of anti-rotational strength prized in modern athletic training, but through an entirely different neurological pathway.

Traditional Chinese martial arts masters often spoke of Zhan Zhuang as "standing meditation," and neuroscience now supports this characterization. Functional MRI studies show that prolonged standing practice activates the insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex - brain regions associated with interoception and body schema. This neural activation pattern explains the enhanced proprioception and movement efficiency reported by long-term practitioners, benefits that directly translate to athletic performance.

The breathing techniques integrated with Zhan Zhuang postures align surprisingly well with modern understanding of respiratory biomechanics. The prescribed abdominal breathing patterns optimize intra-abdominal pressure and spinal stabilization in ways that parallel the bracing techniques taught in powerlifting. However, the martial approach achieves this through autonomic nervous system regulation rather than voluntary contraction, representing a fascinating convergence of ancient practice and modern science.

Perhaps most intriguing is how Zhan Zhuang's emphasis on "rooting" corresponds to contemporary ground force mechanics. The traditional instruction to "imagine growing roots into the earth" creates the precise neuromuscular coordination needed for optimal force transmission through the kinetic chain. Sports scientists now recognize this as essential for everything from punching power to sprinting efficiency, though modern athletes typically develop it through dynamic drills rather than static postures.

Modern interpretations of Zhan Zhuang reveal it as a sophisticated neuromuscular reprogramming tool. The prolonged holds at various joint angles stimulate muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ adaptation in ways that dynamic training cannot replicate. This may explain why traditional martial artists who prioritize standing practice often demonstrate remarkable control during complex techniques - their nervous systems have been conditioned for integrated movement through sustained positional awareness.

The traditional martial arts concept of "jin" (often translated as "trained strength") finds new validation through modern fascial research. The particular way Zhan Zhuang cultivates whole-body connection mirrors current understanding of tensegrity principles in human biomechanics. What masters described as "connected power" now appears to be the optimal functioning of the body's myofascial continuities - a concept only recently embraced by Western sports science.

As research continues, Zhan Zhuang stands as a testament to the sophistication of traditional movement systems. The practice encapsulates principles that modern sports science is only beginning to articulate - neuromuscular efficiency, fascial conditioning, and proprioceptive enhancement all cultivated through deceptively simple standing postures. This convergence of ancient wisdom and contemporary understanding offers exciting possibilities for athletic training, rehabilitation, and general movement education.

Modern athletes and coaches would do well to look beyond the surface stillness of these standing practices. Beneath the apparent simplicity lies a profound understanding of human movement that in many ways anticipated current sports science by centuries. As research methodologies advance, we may discover that traditional masters developed an entire biomechanical language through embodied practice - one that we're only now beginning to decode with our instruments and measurements.

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025

By /Jul 10, 2025